This week I was inspired to go back to the basics, and learn music theory from scratch. Twenty years previously, having just moved to the city of Victoria, BC, I took the opportunity to enroll in two courses at the Royal Conservatory: one in traditional Irish pennywhistle, and one in jazz theory. The theory course was completely over my head, with its advanced treatment of chords, inversions, suspensions and so on. So I stuck to my more simplistic pennywhistle tunes and limited my explorations to modes.

This year, playing with a local singer songwriter kind enough to let me sit in with his practice sessions, I had motivation to try to get better in harmonizing. I did what I could just winging it, playing by ear, mostly trying to guess the key and stick to that scale, following or complementing the melody while trying to avoid too many wrong notes.

Little by little I seemed to get better at sounding good, but progress has been slow, especially given infrequent sessions and lazy practice with recordings, on my part. But there was another impediment, which I could identify as a fuzzy understanding of melodic structure and harmony.

I started digging online to find out more and wound up with a 1099-page PDF called Open Music Theory—self-described as “an open educational resource intended to serve as the primary text and workbook for undergraduate music theory courses.” (Available by free download from: https://viva.pressbooks.pub/openmusictheory/)

I share some of my key takeaways from this crash course in the following sections. All three topics confirm earlier intuitive discoveries I had made on my own, only now I could understand why they had attracted me, and I could access it all in a new, 2-dimensional visual form.

The Magic of the Tonnetz

From linear thinking to 2-D patterns

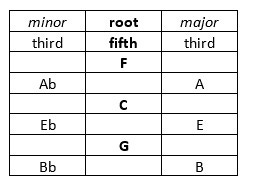

At some point while focusing on basic chords (1–3–5) I realized I could set up a handy vertical chart with three columns, with the root notes (1) in the center, progressing downward by fifths, with the thirds in between on either side, flatted for the minor key, or natural for the major key, like this:

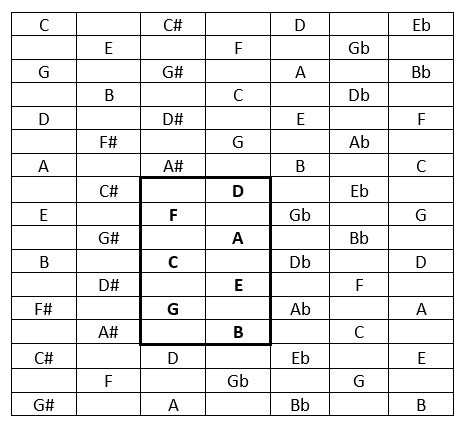

Extending the chart up and down through the whole circle of fifths makes a good quick reference chart, for playing chords and principal intervals: fifths (going down the column), fourths (going up), and thirds (diagonal). But my study of music theory and harmony made it clear that more was needed: a way to visualize how the various scales could interconnect smoothly, by modulating from one key to a neighboring key. So connections could be made horizontally as well as vertically, simply by adding more columns in the same fashion:

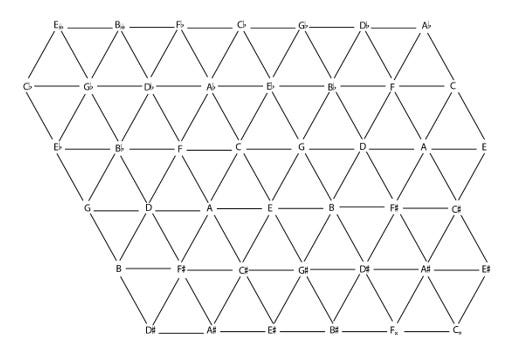

Eventually, about halfway through my reading of Open Music Theory, I found that the same principle wasn’t my clever invention at all. It was called a Tonnetz (for “tone network” in German), first described by Leonhard Euler in 1739 (Wikipedia). Having started to map out areas of the lattice in close proximity, such as the seven notes of the C Major scale (boxed area above), I could now map out many other configurations and shapes, applying the lessons from the textbook. Not only fifths, fourths, and thirds, but seconds, sixths, sevenths and flatted sevenths.

While I set up my grid as a table for convenience, usually the Tonnetz is a lattice of triangles:

Outlining sets of connected triangles produces different unique patterns for all the common song forms of chord progression, the simplest being a IV–I blues progression shown by any two downward pointing triangles side by side; add a third and you have all the notes of a major scale, and the IV, V and I chords of a 12-bar blues. While the major/minor modes are nested together (as in the C major box in my table grid), other scales such as the Harmonic Major or Harmonic Minor are more asymmetrical.

To be continued…