Flat Flute Theory

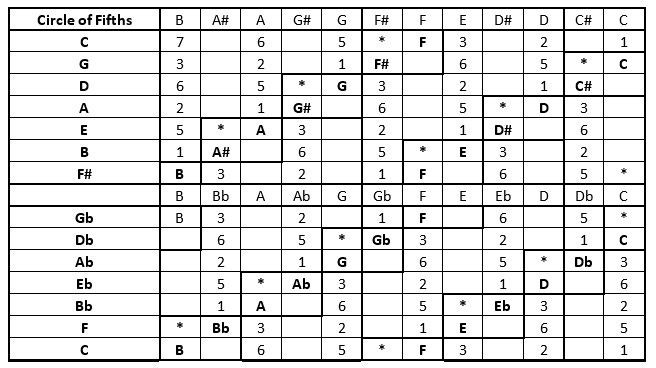

Lately when improvising I’ve been fascinated by resolutions on the 7, or Locrian mode, and finding a corresponding tonic center on the 3, or Phrygian mode. It’s not a resolution in the conventional sense, as with a major, dominant or minor mode. More of a melodic tension that is held, even sustained at the end without the more rooted resting place.

Focusing on the 7 hole is also useful in navigating melodic progressions down the Circle of Fifths, since it’s the one note that changes in a downward shift, flattening and becoming a 4 in the new key (e.g., moving from F# to F when shifting from G to C major).

Moving up the chart, as from C to G, it’s those 4/7 positions that indicate each new sharp note: first F#, then C#, then G#, and so on. So again it’s a useful place in each scale to focus on, to differentiate each scale from its nearest neighbor.

Meanwhile a stronger tonal center is expressed by the 3—consistently, I find, across almost all the scales. I suppose it’s natural as an intermediate pivot between the stronger 1 root or 5 dominant center. The 3 also happens to be a strong fifth interval away from the 7 (or fourth interval, going the other direction). Using all three correspondences yields the ubiquitous I - IV - V progression, or ii - V - I. These are equivalent intervals to 2 - 3 - 6, or 3 - 6 - 7, which helps explain the appeal I’ve been finding in those notes of any given scale.

It's also interesting to notice my evolving taste away from the Lydian (4) and Major (1) tonal centers, further down the Circle of Fifths in the following order: 4, 1, 5, 2, 6, 3, 7 (for example, starting from F in the key of C, then in F Major, Bb Major, and so on). I began my flute studies with the Dominant (5) and Dorian (2) flavors of Irish pennywhistle tunes, fell in love with the minor (6), and lately have been drawn to the 3 and 7 notes in my melodic explorations—both solo and when playing harmony with other songwriters.

Coincidentally, I’ve been trying to soak up a little jazz-blues advice from the weekly newsletters from JazzAdvice.com. Following the 80–20 rule, 80 percent of those lessons are over my head in advanced jazz theory and practice, but I usually find about 20 percent of it useful and applicable to my learning on the flute. This week there was a fair bit of discussion about using the b5 note, and when I plug it into the chart above (*) it appears in the intriguing spot just past the 7 as we continue down (flat) the Circle of Fifths.

Even less stable than the edgy Locrian 7, the b5 has effect as a passing or grace note, a blues nod, a jazz lick. It represents a bridge between the two adjacent keys; and when both the natural and flatted 5 are played together, it’s an eight-note bebop scale. For example, C and G merge when we play G - F# - F - E. The result is D Dorian Bebop, G Dominant Bebop, or F# Prokofiev (among other possible modes of that hybrid scale). Alternatively, the G (natural 5) can be left out of this blue coloring of the C Major scale.

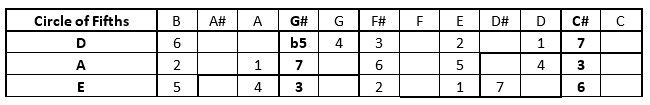

A good exercise is to move both up and down from a given scale, for example from A, down to D and up to E. This is the I - IV - V or ii - V - I combination again, so central to much popular music. But again I prefer to offset the same intervals, playing 3 - 6 instead of 5 - 1 in one scale, or shifting from 3 to 7 between scales, instead of from 1 to 5. To illustrate:

When improvising from the key of A, I tend to highlight the G# (7) and C# (3). I can still lean on those same notes going up to E Major or down to D Major. In E, the C# occupies an even stronger 6 position as the minor, and the G# strengthens from 7 to 3; while the D (4) gets pulled up to D# (7) as another tonal center. Going the other direction, from A to D Major, it’s the G# that normally gets shifted down to a G. Retaining the G# as a b5, however, sustains the flavor of the A Major, while the G pulls downward, flatter for D Major. The combined result is a tasty variety of blues.